Click here to see full infographic.

Corporate culture started shifting in the 1970s, when US scholars promoted the idea of maximising shareholder value (MSV) as a company’s sole purpose. This belief developed by economists such as Milton Friedman and Michael Jensen at the University of Chicago has led to a focus on quarterly earnings and short-term share price as the main basis for investment and business decision-making. The idea has also misled many to believe that shareholders own companies, which is not true under the law of any known country.

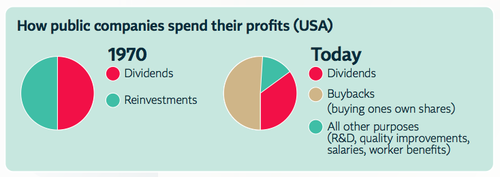

However, MSV is now embedded in business thinking and education, incentivised through regulation and it is pushing companies to extract value instead of creating it. See below some data to illustrate the situation:

- In the 1970s Britain, £10 out of every £100 of profit was paid in dividends to shareholders. Today companies pay £70 out of every £100.

- Many CEOs earn today more than 200 times the wage of the average worker, and CEO rewards salaries are now tied to profits and share prices, ignoring other forms of value.

- Public listed companies consumed 51% of net income in stock buybacks (buying back your own shares), 35% for dividends, leaving just 14% for all other purposes.

The shareholder-centric model has led companies to prioritise short-term profits at the expense of innovation, sustainability, and both employee and societal well-being. It has also been linked to the recent financial crises, thereby putting at risk the long-term health of corporations themselves. This way of thinking has been blamed for some of the worst excesses in corporate behaviour. Side effects of this model are inequality, poverty, environmental destruction and human rights violations. Cases in recent years include:

- BP’s cost-cutting reduced safety oversight and resulted in the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry.

- The LuxLeaks scandal revealed the scope and systemic nature of corporate tax avoidance. Aggressive tax minimisation can have harmful effects on financial performance due to reputational brand damage.

- Volkswagen tampering with car emissions and Toshiba’s accounting scandal proved how an extreme focus on maximising short-term profit deeply affects companies’ decision-making.

- The Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh is an example of cost-cutting in the garment industry leading to human rights impacts in supply chains.

High profile advocates of shareholder primacy such as Michael Jensen (one of the economists who developed the theory), Jack Welch (former CEO of General Electric), and Lucian Bebchuk (Harvard law professor) have backed away from the idea that maximizing share value always and everywhere has the effect of maximizing the total social value of the firm. They now recognise that shareholders may often be incentivised to push directors to take on too much risk, which lifts the share of firm value they capture by imposing costs on creditors, employees, taxpayers, and the economy as a whole.

More recently, Larry Fink, head of Blackrock, the biggest asset manager firm in the world, has reached out to the CEOs of the 500 largest companies in the US to alert on the buybacks escalation and advised companies to focus on long-term business strategies (see letters of 2015 and 2016). In a similar vein, Andy Haldane, Bank of England chief economist, stated that the excessive power given to shareholders was ‘holding back economic growth’.

This critique is also supported by a range of academics who have studied the effects of shareholder primacy. Lynn Stout, Professor of Corporate and Business Law Cornell Law School explains how this business philosophy has led corporate directors to focus on short-term profits at the expense of long-term performance, discouraging investment and innovation and harming employees, customers, the environment and the overall society. Furthermore, William Lazonick, professor of economics at University of Massachussetts (Lowell), links the incentives given to directors to maximise shareholder value with the escalation of share buybacks in the last 30 years. Lazonick demonstrates how this financial practice is in effect counterproductive for companies and harmful to the general economy.

The MSV idea has been reflected and debated mainly in the Anglo-American space where it originated. However, it significantly influences markets and companies in continental Europe and other parts of the world due to financial globalisation and the efforts of the EU and the OECD to harmonise corporate governance.

Purpose as a cornerstone for healthy corporations

The purpose of a company is whatever its founders wish it to be, as long as it is legal. Thus, it might be to make innovative products, develop cutting edge technology, build a spaceship, create the next penicillin, foster a great working environment for employees, satisfy their customers or one of many other objectives. A corporation may also decide to maximise profits and share price - the key here is that it is a permitted objective, not one that is required by law. The definition of purpose will drive business strategies and define their goals and milestones.

Directors have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of ‘the company’, which even if difficult to ascertain, cannot be equated for a normal company with maximising shareholder value, and especially not in the short-term. Shareholders have certain rights in the company and deserve fair returns, but focusing only on quarterly earnings may lead a company to make decisions that will have a negative impact on the future health of the firm, e.g. laying off workers or failing to invest in research and development. Directors are free to instead choose to invest in innovation, research and development, employee training, improvements to sustainability or other areas if that will ensure the long-term vitality of the firm.

What does good corporate governance look like?

A well-run company is sustainable, is managed in a transparent and responsible way and is accountable to high standards that govern its performance in all applicable areas, including the environment, human rights, labour, and tax. Good corporate governance allows a company to anticipate challenges and opportunities, build its capacity to create value on an ongoing basis, embrace the creation of real value for customers and wealth for shareholders as mutually reinforcing objectives, and commit to societal and environmental sustainability.

There are significant advantages to this approach to corporate governance, including better relations with stakeholders, less litigation and fewer costly disputes, and reduced interference from regulatory authorities. Good corporate governance also results in superior performance on the market for products and services as well as on capital markets - at least in the long-term.

Overall, it provides the conditions for successful long-term business operations. Several studies and reports prove the points mentioned above:

- Research by professors at Harvard and London Business School concluded that firms with good performance on material sustainability issues significantly outperformed traditional companies over the long-term, both in terms of stock market as well as accounting performance.

- Research by The KBA Consulting Group has revealed that 59% of the wealth created for shareholders by top performing ASX 100 listed companies over the past five years came from increasing the sustainability of those businesses, namely from extending the length of the Bow Wave of Expected Economic Profits by an average of 25 years.

- Researchers at the University of Hamburg and Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management analysed 2,250 studies over the last 40 years concluding a positive correlation between ESG criteria and strong corporate financial performance.

- According to a Harvard Business Review and Ernst & Young report, 87% of 500 global executives declared that purpose is key to success. However, less than half of the executives integrated purpose into strategy making. The report also shows that in organisations where purpose had become a driver of strategy and decision-making, executives reported a greater ability to deliver revenue growth and drive successful innovation and ongoing transformation.

- The latest UN Global Compact–Accenture CEO study found that 93% of the 1,000 CEOs interviewed across 103 countries and 27 industries see sustainability as important to the future success of their business. Moreover, 78% see sustainability as an opportunity for growth and innovation.

The path ahead for sustainable companies

To achieve sustainable development and long-term stable corporations, we need to debunk the myth of shareholder primacy and foster systemic change in business thinking.

For change to happen, governments need to rethink their approaches to corporate regulation, which, despite being driven by good intentions, still serve to strengthen capital market dominance over corporate strategy. It is essential that we shift the policy discussion from a single-minded focus on shareholders to a more holistic understanding of their role in the firm.

Revisioning corporate governance is not an alternative to the regulation of externalities, like pollution, waste, and impacts on human rights. It rather enhances regulation by focusing on the conditions that push companies to blindly prioritise short-term profits and to adopt the means that produce externalities.

The eventual formulation and recognition of a new understanding of the purpose of the corporation will create a space for a discussion on the regulation of externalities and is essential for a change of our economic system as a whole. Vanguard companies and investors are already leading the way. It’s up to all stakeholders to re-imagine and create corporations ready to face 21st century challenges.

*The PDF of the infographic is also available online here.

Video animation

Useful documents:

Concept note of the Purpose of the Corporation Project

Revisioning the Corporation: A Short Guide to Corporate Governance

Corporate Governance for a Changing World: Report of a Global Roundtable Series